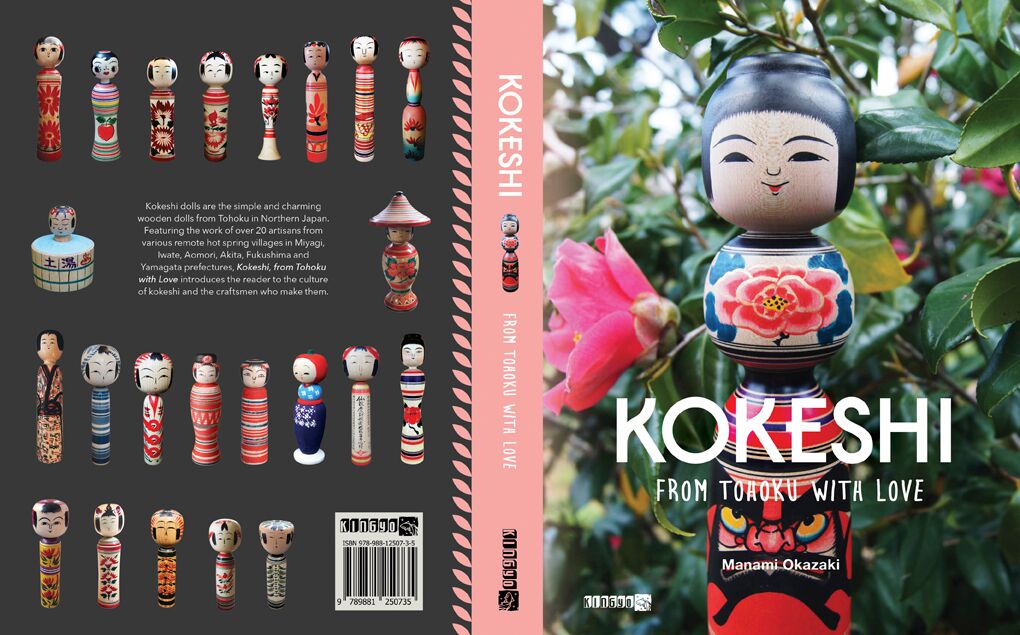

Manami Okazaki has released a second edition of her book “Kokeshi, from Tohoku with Love”, featuring interviews with 23 kokeshi artisans as well as 200 photos documenting how the unique wooden dolls are made in northeast Japan.

Okazaki, the author of several books about aspects of Japanese culture, from tattoos to toy cameras, wrote the first edition as a charity project. It sold out in 18 months and now is available again in a new expanded version.

We spoke to her about her new book.

Q. Why did you choose to write about kokeshi?

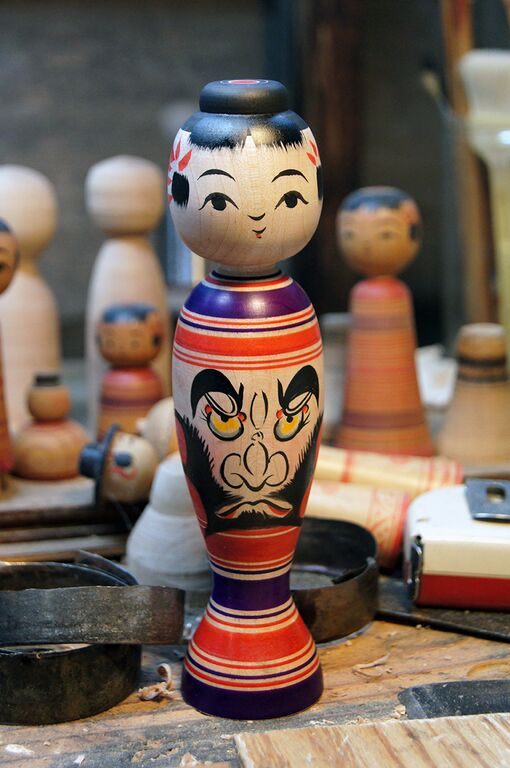

Manami Okazaki: There are a couple of reasons. When I was interviewing people for a previous book I wrote on kawaii culture, many mentioned kokeshi as having the same design sensibilities as modern cute character design. Designers such as Bukkuro (known for designing the Taiko no Tatsujin game) find kokeshi designs inspirational. Traditional types of kokeshi, like a lot of kawaii characters, lack any facial expression (famously, Hello Kitty doesn’t have a mouth), and their simplicity leaves a lot to the imagination.

Since 3/11, the country began to focus on the Tohoku region, and kokeshi became a kind of mascot for the region. There were exhibitions at trendy places like Claska and PARCO gallery, events in Koenji, and a slew of gorgeously designed publications like “Kokeshi Jidai”, which all instigated a boom in kokeshi culture. I write a lot about kawaii culture in any case, and kokeshi aligned with the notion of shibu kawaii (subdued, old school cute).

Last but not least, my grandparents on my mum’s side lived in Onagawa post-war, and my mum grew up there. I am really grateful I experienced Japanese rural life there, and have great memories of visiting them. We also went to Naruko and kokeshi studios when I was a kid, so there is a sense of nostalgia for me as well. I should also add that my mum’s childhood home was swept away in the tsunami, and in an instant, many people died, and the town she grew up in disappeared. When I went up post-tsunami, the playground I used to play in was lined with coffins.

Nothing in life is permanent, but books leave behind a legacy that carries on for generations — it is one way to leave behind a culture. It is not the only way, of course, there is a scholar who did her doctoral dissertation on kokeshi, and there are also documentaries, but it is the way I am familiar with.

Q. Why do you think the first print sold out? Why is there a strong interest in kokeshi?

Manami Okazaki: I think there was just a hole in the market, there are some books which are beautiful, but have little to no text and, are a decade old, and expensive.

The book is in English, so it is intended for an audience abroad — a lot of people recognize kokeshi, and like them, but in reality, a lot of the items that are called “kokeshi” in English are plastic mass-produced products in the likeness of geishas. If you do a google image search for kokeshi in English, most of the images are not kokeshi, but kitschy cartoony toys. I met an owner of a kokeshi shop in Paris who had never seen a real kokeshi in his life, and was asking where he can get wholesale quantities!

I think people were curious to know what these well-known dolls really were. I think there is also a general interest in artisan culture due to things like the slow life movement, and influential taste-makers like Kinfolk and Monocle magazine celebrating crafts.

They are imperfect, as they are made by hand, and each one is different. Asides from that, they are very cute!

Q. What do you think the role of kokeshi is for Japan today? As crafts? Design? Toys?

Manami Okazaki: Mainly as interior decoration items and souvenirs. They started as a kids’ toy, and girls were dressing them up and carrying them on their back. During the Showa era, adults became enamored in them, instigating the first “kokeshi boom”. Tadao Watanabe, a kokeshi artisan in Fukushima told me, “Suddenly, these toys became a thing for urban intellectuals, and they would take dolls out of kids’ hands!”

They are also connected to tourism — they are a souvenir from the hot spring villages in Tohoku where they are made, and people would travel around collecting them. In the Showa era it was “collectors with big backpacks”. Nowadays it is Shimokitaza type, crafty and designer-y young females.

Q. What are the challenges facing kokeshi culture today?

Manami Okazaki: Primarily, the lack of successors and the aging demographic of the current artisans. The apprenticeship is grueling and lengthy, and there is little financial incentive to become a kokeshi maker. It is the same for all the artisans in Japan, across the board.

Q. What are some of the most unusual kokeshi you have encountered? And the most innovative?

Manami Okazaki: Prior to this kokeshi boom, a lot of young people thought that orthodox kokeshi with their demure expressions looked a bit creepy. In response, artisans usually make two types: the very traditional types that are true to their lineage, and ones that are hyper cute — with hats, in the shape of cats, sitting on beer barrels, with manga eyes, and so on. Recently, fashion retailer BEAMS collaborated with kokeshi maker Yasuhiro Satou, using both artificial blue ink, and indigo, as Japan has a rich heritage of indigo dying. Blue is never found in traditional kokeshi, so it was dubbed the “denim head” and they sold an incredible amount!

By and large, they are artisans, not artists though, and their main interest is in dutifully protecting their heritage. They try and “catch” new customers by making hyper kawaii types, in the hope that these some customers eventually get deeper into kokeshi culture, and go for the traditional types. This is something I also saw in the kimono industry as well; the casual, creative styles were seen as a bridge to the “real thing”.

Q. Have you made any significant changes/additions to this second edition?

Manami Okazaki: Yes. It is a second edition ,though, not a new book, so please keep this in mind if you have the first edition. The second edition has all the bells and whistles. It has a thick, textured hard cover, 100% FCS paper from sustainable sources in Europe, two times higher grade paper, larger format, 60 more photos, 3 more profiles, sections on how to buy kokeshi, and added information on Tohoku folklore.

Q. Why did you make the first edition a charity project?

Manami Okazaki: I think it makes sense as kokeshi are from Tohoku. Post-tsunami, almost everyone I knew was working on charity projects, and chipping in where they could, from making books to hosting band gigs and holding charity events. I felt there was a shift in consciousness amongst young people, and a reassessment about the way they (over) consumed. I remember around ten years ago, if you told someone to watch their water consumption, not use so much plastic or packaging, and whatnot, they would think you were a hippie (I’m exaggerating, but not by much). I don’t think many mainstream young people prior to 3/11 had even thought about charity, but everyone I knew, from fashion houses to underground artists were doing something.

It was a charity book, but mostly I am hoping it inspires people to visit these charming hot spring villages and to check out Japan’s artisan crafts. Kokeshi tourism is a really great way to experience rural Tohoku culture, and see craftsmen at work in their own studios.